St. Francis (1181-1226) is one of the most well-known figures in Christian history. He is most renowned for his love of animals and nature, and for having founded the Franciscan Order of Monks. Like St. Augustine before him, he was caught up in a wild and worldly life before coming to religion, and he is revered for the kindness and devotion that he demonstrated thereafter. What is less known about him is his relationship with the Eastern and the Muslim world which, at that time, represented a great rival to Christendom.

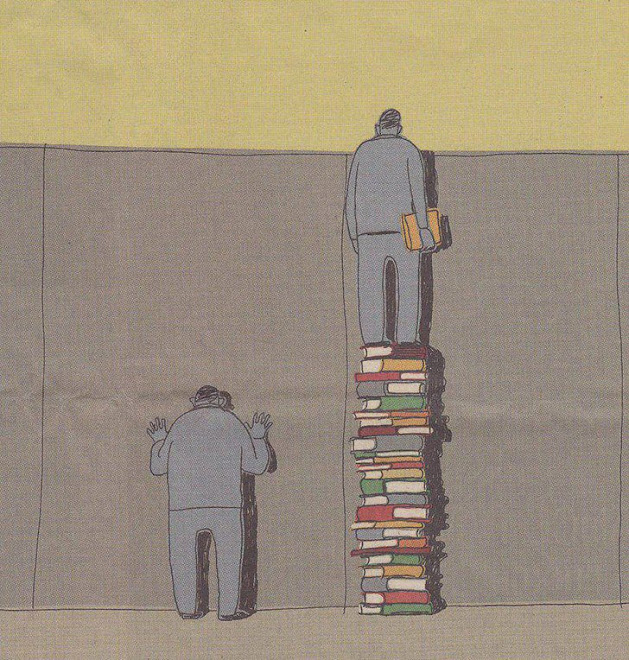

The story of St. Francis is yet another example of the interweaving of eastern and western currents during the Middle Ages, especially those moving from a vibrant Islamic civilization to a burgeoning Europe. This mixing and fertilization was especially evident in Italy and Spain, which directly abutted the Muslim world. Among these currents on the southern shore of the Mediterranean were the Sufi schools of human development.

St. Francis's connections with the East may have begun early in life. He was very interested in the Troubadours of Provence during his youth and may have been influenced by their way of life. They, in turn, were likely derived from Islamic culture (the etymology of the word 'troubadour' is disputed, but it is unusually close to the Arabic word 'tarab', which means a kind of transcendence through music). Later, he exhibited a keen interest in travelling to the Muslim world. He attempted to go east to Syria, but managed only to get to the Dalmatian coast of what is now Albania. He then tried to go west to Morocco, but ended up in Spain.

In 1219, St. Francis did finally succeed in an eastern journey when he reached the city of Damietta in Egypt, which was then besieged by Crusaders. St. Francis crossed from the Crusader to the Saracen side of the Nile to meet with the Sultan Malik el-Kamil. The traditional explanation is that he did so in order to convert him to Christianity, but failed in his effort. There are indications however that his purpose was different.

He was well received by the Sultan and permitted to preach in his lands. Upon returning to the Christian armies, St. Francis did his utmost to dissuade the Western knights from attacking the Muslims. He was ignored and the result was a Crusader defeat at the walls of Damietta. Since the fall of the Crusader kingdoms in the Middle East, only the Franciscans have been permitted to be the "Custodians of the Holy Land" on behalf of Christianity.

In subtle ways, he (and many others in his time) may have symbolized a broader current of human development than either the outward forms of Christianity and Islam can convey. He and the Sufi poet Rumi, for example, were contemporaries and share strong similarities in their poetry.

St. Francis even more closely paralleled the Sufi Najmuddin Kubra, the founder of an order called the 'Greater Brothers' (the Franciscans were also known as the 'Minor Brothers'). Sixty years before St. Francis's birth, Najmuddin was known for his love of animals, and for having tamed a fierce dog - as the Christian saint was later to do with a wolf.

Indeed, one of St. Francis's major contributions was to infuse a more democratic and "grass roots" movement into a very hierarchical church. He refused to become a priest, and returned the faith closer to the people, and away from institutions and authorities - a characteristic that has defined the Franciscans ever since.

Among his other many achievements, St. Francis, with his love for nature as the mirror of God and for animals as his "brothers and sisters", created the idea of the manger or nativity scene for Christmas, a symbol still very much alive today.

Like many other saints, St. Francis has been depicted in a variety of ways throughout history.

Like many other saints, St. Francis has been depicted in a variety of ways throughout history.