For every Mandaean living in Iraq today, there were twelve living there in 2003. What was once a population of 60,000 has dwindled to 5,000 as they fled their ancient homeland for the safer grounds of Australia and America.

What is a Mandaean?

The Middle East is a much more complex and complicated stew of ethnicities than the sound bytes in the news convey. Beyond the Arabs and the Israelis, and the Shiites and the Sunnis are many other groups, including the Chaldaens, Kurds, Alawites, Armenians, Yazidis, Maronites, Sephardic Jews, Ismailis, the Assyrians, the Bahais - and the Mandaeans.

The region is interspersed and enriched by these small and often very old communities that have maintained their way of life for centuries and millennia. Many of them are a testament to the manifold attempts at religious understanding that have sprouted in the Middle East since the dawn of civilization.

The Mandaeans gain their name from the Aramaic word "manda", meaning "to know". They are an ancient religious group whose origins are disputed. Some believe they are a sect that left Judea after the destruction of the Jewish Temple in the 1st century A.D. Others speculate that they came from southern Iraq in the 2nd century. Some insist it was a combination of both sources.

Today, they are often cited as one of the few vestigial "Gnostic" groups - people who pursue understanding of the divine through self development, and, ultimately, a direct knowledge (gnosis) of truth. Hence, the origin of the term "Mandaean", or literally, "The Knowers".

They worship, among other prophets: Adam, Noah and St. John the Baptist. They believe the latter to be the authentic prophet of his time, rather than Jesus. Their rites revolve around 'baptism' and 'ascent' - both of which involve the use of running water for ritual purifications.

The purpose of baptism is the expiation from sin and a communion with light, while ascent is performed when a Mandaean dies to assist his or her soul to rise to the world of light. It involves cleansing with running water, anointing with oil, and placing of a crown of myrtle on the adherent's head. In both cases, the living waters represent the higher world of transcendence and greater reality.

Their theology is described as dualistic, involving good versus evil. But it is more complex than that label. It is well articulated in the following passage:

"[They] believe in a supreme being, without form, who produced spiritual powers and worlds from its own being. They declared that among these emanations are creator gods, including archetypal man, who produces the material Universe. They portray each human soul as a captive, an exile whose home and origin is the supreme Entity to which the soul eventually returns." [1]

Whether the Mandaeans are any more truly and actively gnostic, directly partaking in the great truth of life, is a matter of conjecture. Their disappearance from Iraq and their diaspora remains, nevertheless, a sure and hard reality and a tragic testament to the intolerance that swept that country after the American invasion in 2003. They were persecuted heavily by religious extremists in Iraq, and had to undergo forced conversion.

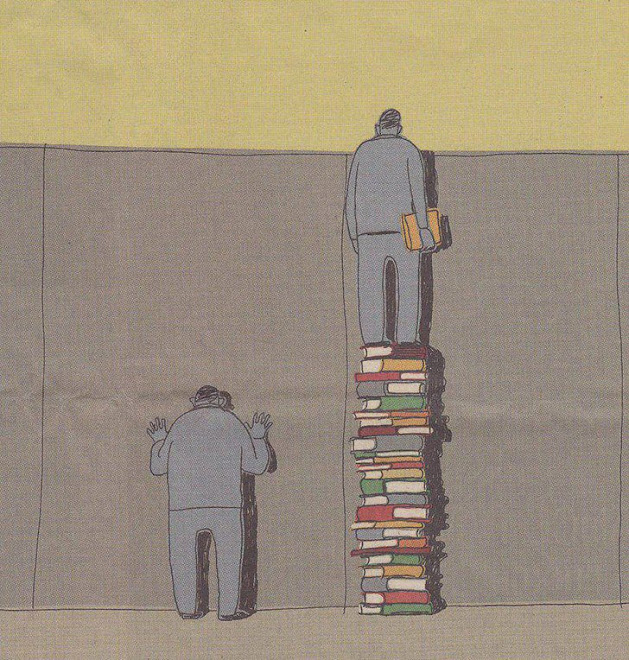

The suffering of the Mandaeans is a lesson in the dangers of a monopoly on truth, or a belief in the supermacy of one's faith. The inevitable logic of such views is the persecution of others.

Their disappearance from Iraq is also a reflection of the ignorance of the spiritual path called "gnosis", or knowledge of the truth. This critical current of human development, once rare and hidden, may now have to become a universal and common project in order for our species to survive and evolve.

[1] Godhead: The Brain's Big Bang, by Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell, HG Publishing, p. 400.