Mention to anyone in the Middle East that your family comes from a town in Turkey that was once a part of Syria, and is today located just north of the Syrian border, and you will invariably be told that you must be from either Iskinderun or Antakia. A good guess. But travel 200 odd miles east along the Turkish-Syrian frontier from either of these former Syrian cities, and you will reach an unusual-looking hillside town with a commanding southern view over the baking Mesopotamian plain.

This is Mardin, a city of pigeon flocks and old stone homes situated on the far cusp of the Arab world. It is also a place that is strangely unknown to the vast majority of Middle Easterners. Located in the heart of the Kurdish-populated southeast Anatolia region of Turkey, Mardin was up until recent times a kind of microcosm of the Middle East. An important Silk Road station, the town brought together disparate ethnic communities from all across the interior of the Levant, Northern Mesopotamia, Iran, and the Caucasus. These included Syrian and Bedouin Arabs, Turks, Kurds, Armenians, Jews, Assyrians, Nestorians, Yezidis, Chaldeans, Syrianis, Nestorians, Chechens, and Turkomen - all of whom shared the tiered cobblestone byways of the city's old Arab medina built of a light coloured amber stone.

Mardin was the northernmost outpost of Arab culture before the deep hinterland of the non-Arab Middle East began - those rugged mountains where the flanks of the Turkish and Iranian empires collided and mixed with the Kurdish and Armenian nations to form a primeval confluence of blood and belonging. All non-Arabs that settled in Mardin were inadvertently Arabized as though by some strange and unexplained law of nature. A typical “Mardeli” (the word denoting a person hailing from Mardin) spoke a brusque dialect of Levantine Arabic (also called “Mardeli”) that was as coarse to most Arabs as the Sicilian dialect of Italian is to most mainland Italians today.

From its establishment as a strategic outpost in early antiquity, Mardin has always been a frontier town in the truest send of the word. It has manned the edges of numerous cultural empires whose beginnings and ends were measured and marked by the transitions between peoples. Babylonians, Hittites, Assyrians, Urartians, Persians, Romans, Arabs, Selcuk Turks, Mongols, and Ottomans all made use of this hillside perch that dramatically announced the end of the plains and the beginning of the mountains.

But with the coming of the modern age, as tribes and nations adopted or were forced to accept the practice of strictly demarcating their territories, Mardin fell into decline as a multi-cultural experiment without borders. The political upheavals of the early 20th century - massacres and ethnic resettlement programs - sent the Mardelis packing. They were scattered like seeds in the wind to places all across the Middle East - to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and beyond. These were countries where they would be resettled and assimilated, but where deep inside they would belong to no place in particular - embodying instead, intangible notions and genetic memories of a rural cosmopolitanism based on tolerance.

But with the coming of the modern age, as tribes and nations adopted or were forced to accept the practice of strictly demarcating their territories, Mardin fell into decline as a multi-cultural experiment without borders. The political upheavals of the early 20th century - massacres and ethnic resettlement programs - sent the Mardelis packing. They were scattered like seeds in the wind to places all across the Middle East - to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and beyond. These were countries where they would be resettled and assimilated, but where deep inside they would belong to no place in particular - embodying instead, intangible notions and genetic memories of a rural cosmopolitanism based on tolerance.

Today, even more than in Mardin itself, echoes of that past can be seen and heard in Mardin's satellite towns of northeast Syria where some semblance of that original admixture of peoples - the "Mardelis" - still resides: towns like al-Qamishle, Hassake, and the Euphrates River town of Deir al-Zor.

The pigeons, the old stone palaces, and murmurs of a dilapidated Arabic still abide in Mardin - but under the watchful gaze of a Turkish military garrison peering suspiciously across the frontier into Syria and engaged in an unresolved local conflict between cultures that once knew few divisions.

The coast has always attracted humans. They emerge from the adjacent hills and valleys to try their luck in the waters. This scene is repeated on the coasts of Brittany, Malabar, or Batan. Here is a scene from Beirut at sunset.

The coast has always attracted humans. They emerge from the adjacent hills and valleys to try their luck in the waters. This scene is repeated on the coasts of Brittany, Malabar, or Batan. Here is a scene from Beirut at sunset.

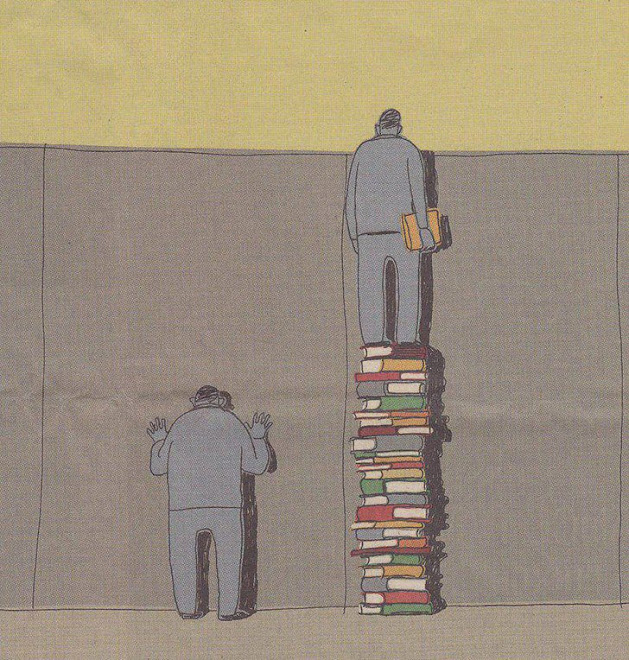

Review: The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In, by Hugh Kennedy, 376 pages, Da Capo Press.

Review: The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In, by Hugh Kennedy, 376 pages, Da Capo Press.