If you ask people familiar with the Middle East to list the towns with the best souqs, bazaars, and old medieval quarters, you’d find yourself - more or less - confronted with the same gang of seven places, being: the old city of Damascus; Fatimid and Islamic Cairo; the Grand bazaar in Istanbul; the Medina of Fez; old Sana’a in Yemen; the souq in Aleppo; and of course, the old city of Jerusalem.

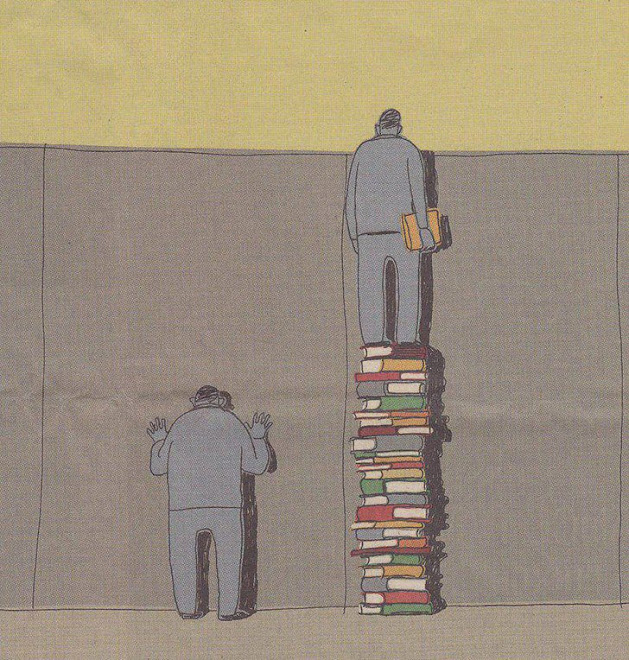

These spots, which constitute a sort of A-list of living-breathing antiquity, are some of the most evoking in the region. Anyone who spends enough time in the Middle East will often have a favourite among them. But a recent trip to a little-known city in southeastern Turkey left me with the impression that one site has been improperly left out of the mix.

About an hour’s drive north of the Syrian-Turkish border is the ancient city of Şanliurfa. Located on the cusp of Mesopotamia, it’s one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world (a title claimed by both Damascus and Erbil, in Iraq). Şanliurfa, still known today by its old name of “Urfa”, is so ancient that the legendary Biblical figures Abraham and Job - archetypal characters residing in the deepest collective memory – are said to have come from there.

It’s not surprising therefore that the city has a first-class labyrinthine old town and bazaar, that is largely unknown and only visited by a smattering of Muslims who come from abroad on pilgrimage to visit sites tied to the Biblical patriarch.

Part of what makes the place so special is its hybrid feel. Although mostly inhabited by Kurds and Turks, Urfa has a very Arab character. Like its nearby sister cities of Antakya (formerly Antioch), Gaziantep (formerly Antep), and Mardin, Urfa was once a bastion of Middle East multiculturalism that blended not only Kurds and Turks but also Armenians, Syriacs, Syrian Arabs, Bedouin, Greeks, Jews, Turcomen and Assyrians. In 1984, Turkey’s parliament officially changed Urfa’s name to Şanliurfa (meaning “Urfa the Glorious”) in order to commemorate the fighting prowess of its residents during the country’s war of independence.

Travel a short distance south of the city and you’ll also encounter tiny agricultural villages whose ways of life have not diverged an iota from the time of ancient Mesopotamia. Near to these cluster of settlements is the famous ancient mud village of Harran and the recently discovered 12,000 year-old archaeological site of Göbekli Tepe – one of the oldest and most important ancient sites in the world.

Below are some more images taken in Urfa’s old city: