Saturday, December 29, 2012

Tuesday, December 25, 2012

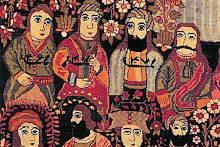

The Hakawati

A hakawati is a storyteller in Arabic, and also the title of a book by Rabih Alameddine, a Lebanese-American writer. This weave of stories, told by many "hakawatis", range from fantastic battles between demons and enchantresses, to the mundane collapse of Beirut in civil war. Its great hidden virtue is that it is also a one-shot window, through time and space, onto the many flavours and cultures of the Middle East.

Alameddine takes us to Urfa at the turn of the last century, with its Armenians, European missionaries, and the local obsession with competing flocks of pigeons; he dives into the beginnings of Mamluke Cairo and the rise of Baybars - the slave-turned-king and slayer of Mongols and Crusaders; he then veers to the Kharrat family in Lebanon, a Druze clan that made its money through its Japanese car dealership.

The book is the story of storytellers, and their stories, all interlaced to take the reader through centuries of the region, its fantasies and its harsh realities. Demons, colorful imps with the names of prophets - violet Adam, indigo Elijah, blue Noah, and green Job - robbers, thieves, and modern warlords compete in the pages with vain women and envious men.

Through it all, the writer manages to reflect the very incomprehensible nature of the region: colourful, dramatic, full of high emotion and dark prophets laced with the occult. It is a great story - or many stories - yet it is somehow bereft of any seeming purpose or end. Indeed, storytelling is a great tradition in the Middle East, and in the lands further to the east. The classic hakawati sits upon his throne in a cafe, often wearing a tarbouch or fez, regaling his listeners with tales that can go on for hours. This book strives to capture the beauty of that art, revealing that what matters is the tale itself, and the quality of its telling rather than some higher purpose. As with so much in the Middle East (possibly too much), the meaning is in the weave, whatever its content.

'The Hakawati' builds and constructs these half dozen stories over four sections, and one wonders where they will all go. In the last section, however, Alameddine shows he knows the art of ending, closing several tales like doors that suddenly and firmly shut. What seemed like lyrical fantasies begin to stand on more sober ground: Baybars is really no hero but a cunning self-promoter; the narrator's entrancement with Beirut is now but a cold and barren reality; and the demons' battles come to a harsh and incomprehensible closure.

The author ends the book with a touching moment, the narrator, coming to terms with a troubled relationship with his father, promises to tell his stories at his dying parent's hospital bed. The tale goes on; no matter the shifting sands and passing of lives - the hakawati does not stop.

Alameddine takes us to Urfa at the turn of the last century, with its Armenians, European missionaries, and the local obsession with competing flocks of pigeons; he dives into the beginnings of Mamluke Cairo and the rise of Baybars - the slave-turned-king and slayer of Mongols and Crusaders; he then veers to the Kharrat family in Lebanon, a Druze clan that made its money through its Japanese car dealership.

The book is the story of storytellers, and their stories, all interlaced to take the reader through centuries of the region, its fantasies and its harsh realities. Demons, colorful imps with the names of prophets - violet Adam, indigo Elijah, blue Noah, and green Job - robbers, thieves, and modern warlords compete in the pages with vain women and envious men.

Through it all, the writer manages to reflect the very incomprehensible nature of the region: colourful, dramatic, full of high emotion and dark prophets laced with the occult. It is a great story - or many stories - yet it is somehow bereft of any seeming purpose or end. Indeed, storytelling is a great tradition in the Middle East, and in the lands further to the east. The classic hakawati sits upon his throne in a cafe, often wearing a tarbouch or fez, regaling his listeners with tales that can go on for hours. This book strives to capture the beauty of that art, revealing that what matters is the tale itself, and the quality of its telling rather than some higher purpose. As with so much in the Middle East (possibly too much), the meaning is in the weave, whatever its content.

'The Hakawati' builds and constructs these half dozen stories over four sections, and one wonders where they will all go. In the last section, however, Alameddine shows he knows the art of ending, closing several tales like doors that suddenly and firmly shut. What seemed like lyrical fantasies begin to stand on more sober ground: Baybars is really no hero but a cunning self-promoter; the narrator's entrancement with Beirut is now but a cold and barren reality; and the demons' battles come to a harsh and incomprehensible closure.

The author ends the book with a touching moment, the narrator, coming to terms with a troubled relationship with his father, promises to tell his stories at his dying parent's hospital bed. The tale goes on; no matter the shifting sands and passing of lives - the hakawati does not stop.

Tuesday, December 18, 2012

Saadi of Shiraz

Most people in the West have heard of the poets Omar Khayyam and Jalaludin Rumi. Khayyam came to Western fame through a (poor) 19th century translation of his now-famous Rubaiyat, and Rumi is today a rock star of new age spirituality and mystical literature. Fewer people have heard of Hafez or Saadi, two Persian poets from Shiraz who are more well-known in Iran than the aforementioned pair.

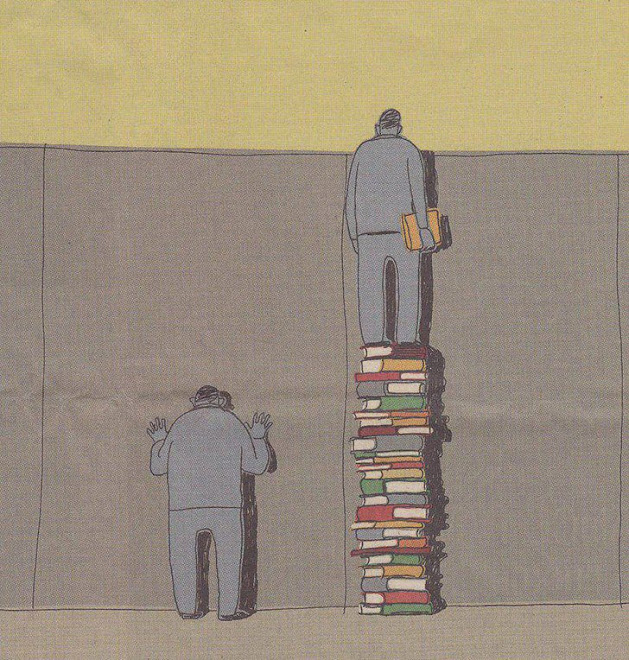

The more interesting and comprehensive outlook is to see all these writers as one stream of excellence extending from the 11th to 14th century, and bringing to the planet some of the most intelligent and insightful texts the world has known. The Persian poets are as seminal to world literature as the ancient Greek playwrights, Shakespeare, or 19th century Russian literature, but they are less well known in the West. They are part of an unstated 'global canon' of overlapping universal themes that recur in all cultures: aids for greater learning.

Saadi lived in an era of incredible violence and upheaval. European Crusaders had invaded the Levant, and the Mongols were devastating the lands further east. In 1226, Saadi left his home to tour the world. As you might expect, it was not without adventure. While criss-crossing North Africa and the Middle East, he married twice, apparently in Aleppo and Yemen, and was enslaved for awhile by the Crusaders.

He left us with two great works among many others, the Bustan (The Orchard), and the very famous Gulistan (The Rose Garden), two works of travel, keen observations, and commentary, set in poetic style. Both works are deeper repositories of knowledge, of the human travels to deeper consciousness, and of our larger purpose.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great American poet and essayist of the 19th century, understood the power of Saadi, and wrote a great poem about him, his character, and his outlook on life. Emerson also wrote an introduction to a translation of Gulistan, in which he wrote:

"The word Saadi means fortunate. In him the trait is no result of levity, much less of convivial habit, but first of a happy nature... easily shedding mishaps... and with resources against pain. But it also results from the habitual perception of beneficent laws that control the world, he inspires in the reader a good hope."

After thirty years on the road, Saadi returned to his native Shiraz. One year later, Halagu Khan and the Mongol horde sacked Baghdad annihilating the Abbasid empire. Saadi died in Shiraz at the age of 83, and his words live on to this day. One of his most famous verses is often quoted in speeches and is also found in the Hall of the United Nations in New York.

The more interesting and comprehensive outlook is to see all these writers as one stream of excellence extending from the 11th to 14th century, and bringing to the planet some of the most intelligent and insightful texts the world has known. The Persian poets are as seminal to world literature as the ancient Greek playwrights, Shakespeare, or 19th century Russian literature, but they are less well known in the West. They are part of an unstated 'global canon' of overlapping universal themes that recur in all cultures: aids for greater learning.

Saadi lived in an era of incredible violence and upheaval. European Crusaders had invaded the Levant, and the Mongols were devastating the lands further east. In 1226, Saadi left his home to tour the world. As you might expect, it was not without adventure. While criss-crossing North Africa and the Middle East, he married twice, apparently in Aleppo and Yemen, and was enslaved for awhile by the Crusaders.

He left us with two great works among many others, the Bustan (The Orchard), and the very famous Gulistan (The Rose Garden), two works of travel, keen observations, and commentary, set in poetic style. Both works are deeper repositories of knowledge, of the human travels to deeper consciousness, and of our larger purpose.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great American poet and essayist of the 19th century, understood the power of Saadi, and wrote a great poem about him, his character, and his outlook on life. Emerson also wrote an introduction to a translation of Gulistan, in which he wrote:

"The word Saadi means fortunate. In him the trait is no result of levity, much less of convivial habit, but first of a happy nature... easily shedding mishaps... and with resources against pain. But it also results from the habitual perception of beneficent laws that control the world, he inspires in the reader a good hope."

After thirty years on the road, Saadi returned to his native Shiraz. One year later, Halagu Khan and the Mongol horde sacked Baghdad annihilating the Abbasid empire. Saadi died in Shiraz at the age of 83, and his words live on to this day. One of his most famous verses is often quoted in speeches and is also found in the Hall of the United Nations in New York.

Human beings are members of a whole

In creation of one essence and soul

If one member is afflicted with pain

Other members uneasy will remain

If you have no sympathy for human pain

The name of human you cannot retain.

Monday, December 10, 2012

Mona el-Hallak and the Barakat Building

For over a decade, Lebanese architect Mona el-Hallak has waged a single-handed campaign to turn a war-ravaged belle epoch building in Beirut into the first museum devoted to the contemporary history of the city.

The museum, which will be called "Beit Beirut", will devote part of its display to addressing the country's devastating 15 year civil war (which lasted from 1975-1990).

Also known as the "Barakat building", the four-story structure sat astride the city’s so-called “Green Line” during the war, which divided the Christian and Muslim quarters of Beirut. It is an area that saw some of the heaviest fighting during those years.

The architect who created the building in the 1920s, designed it in such a way that would later make it a perfect hideaway for snipers during the war - providing depth, safety and a variety of vantage points from which to shoot at passersby on the street. During the war scores of civilians were killed outside its doorsteps.

The architect who created the building in the 1920s, designed it in such a way that would later make it a perfect hideaway for snipers during the war - providing depth, safety and a variety of vantage points from which to shoot at passersby on the street. During the war scores of civilians were killed outside its doorsteps. When real estate developers tried to turn the pockmarked structure into a parking lot in 1997, Hallak launched her crusade to save the edifice from demolition. At the same time she put forward an alternate vision for the building: to turn it into a museum devoted to the memory of Beirut, where visitors could come and learn about the civil war.

It was an ambitious scheme in a country of deep and longstanding ethnic disputes, and where the erstwhile conflict is seldom discussed in any meaningful way.

“After almost a generation of reconstruction there is not one single museum, or centre, that addresses what happened here and how 100,000 Lebanese were killed,” says Hallak. “This project is an attempt to reverse this dangerous collective amnesia among the Lebanese.”

For 15 years real estate developers, politicians, and a public more interested in forgetting the past threw every obstacle into her path. But Hallak’s determination and deft campaign proved too difficult to stymie.

After much toil the project has cleared the final hurdles to construction. Renovation work on the Barakat Building, which began several weeks ago, is slated for completion in 2015.

A full-length Q&A with Hallak about the history of the building and her efforts to save it can be read here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)