"White smoke drifted up from a fog machine... A sound system played...anthems - deep male voices booming to a marching band's rhythms. The parents applauded wildly, the mothers ululating." (1)

We usually reserve the word ¨cult¨ for groups that commit mass suicide by drinking poison-laced purple cool-aid.

There is a view however that cult phenomena are much more pervasive in our lives. In the book 'Them and Us: Cult Thinking and the Terrorist Threat', Dr. Arthur Deikman, a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, explains how cult thinking affects almost all of us. In the Middle East, where group belonging and identity remain supreme totems, the effect of hidden cult behaviour may be especially marked. Understanding its effects there may be critical to moving the region to new and more constructive paradigms.

Deikman points out that cult behaviour has three main characteristics:

We usually reserve the word ¨cult¨ for groups that commit mass suicide by drinking poison-laced purple cool-aid.

There is a view however that cult phenomena are much more pervasive in our lives. In the book 'Them and Us: Cult Thinking and the Terrorist Threat', Dr. Arthur Deikman, a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, explains how cult thinking affects almost all of us. In the Middle East, where group belonging and identity remain supreme totems, the effect of hidden cult behaviour may be especially marked. Understanding its effects there may be critical to moving the region to new and more constructive paradigms.

Deikman points out that cult behaviour has three main characteristics:

- Dependence on a leader;

- Devaluing the outsider; and

- Avoiding dissent within the group.

Compliance to and within groups is a natural human phenomenon, necessary for survival. But group activity can vary greatly, from consensus building and open critical discussion to more cult-like closed systems that reject not only outsiders but also any intruding realities – ultimately much to the expense of the group and its survival.

Taboos and respect and fear for authority are strong features of many groups in the Middle East. From national identity, to religious systems to patriarchal families, respect for the leader, authority or ¨father figure¨ is unquestioned. The values of the society, especially religiously based ones, are taboos that do not sustain critical inquiry. Indeed, in this scenario, the ability to truly see an outsider at ¨eye level¨, i.e. equal, is simply not there.

In the Middle East, these matters are simply seen as "the way things have always been, and will always be". However, this is a method of group survival with potentially terrible consequences in an age of globalization and weapons of mass destruction.

Whether in Israel´s relations to its neighbours, its desperate desire to preserve its identity or assumptions among some about being somehow superior to others, or in Hizballah´s grip on its members, motivating them to higher purpose through sacrifice, even death, cult behaviour continues to grip the region, hidden in the veneer of tradition and references to longstanding cultures and civilizations.

"You are our leader... We are your men!" (2). Indeed, most seductive of all, according to Deikman, is when belonging to a group comes with a divine calling. It makes the mission of sublime importance and eases the ability to maintain the tightness of the group, calling on members to act blindly in its favour. By devaluing outsiders and feeling supreme, the group can provide members with a sense of mission and meaning.

The benefits of belonging to groups that act like cults are many: comfort, security, belonging, and, above all, a sense of higher purpose that the group and leader deliver, often at any cost. Indeed, it is when security and comfort meet higher purpose that the cult becomes an iron-clad contract between individual and group.

The cost of cults is massive. Deikman calls it ¨diminished realism¨. We see it every day in the Middle East:

Certainly, the record of progress in the Middle East is testament to a state of ¨diminished realism¨. It may not be at all impossible for Israelis and Palestinians to come to terms if certain taboos are sacrificed, i.e. if cult behaviour is recognized and reduced.

Cult behaviour does not just apply to religious or Middle Eastern groups. It appears in a more subtle fashion in companies, organizations, and even between friends. The difficulty is that devaluing outsiders, avoiding dissent and blindly obeying leaders is often unrecognized for what it is. Furthermore, the reality is that breaking out of the group can be terrifying. Being thrust out, "excommunicated", a heretic in one's own "family" - however understood - can mean that the most basic instincts of life or death are triggered.

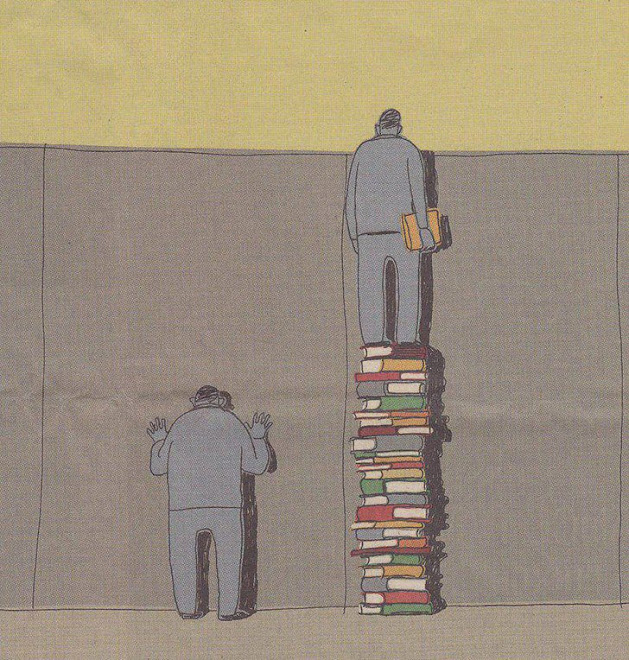

Yet, ironically, the word 'heretic' is derived from the Greek 'hairetikos', meaning 'able to choose'. Indeed, many in the Middle East deny the possibility of choice and point to the dance of fate in their desperate destiny, where in fact longstanding and unconscious acceptance of cult behaviour may be at play. After all, no one really wants to be a heretic.

Developing awareness of the problem is not easy, but it is possible. Recognition of one´s own cult tendencies may be the beginning.

"The musk oxen gather in a circle to defend against the wolves yet there may be only other oxen outside the circle."

(1) "Hezbollah Seeks to Marshall the Piety of the Young", New York Times, November 21, 2008

(2) Ibid.

Taboos and respect and fear for authority are strong features of many groups in the Middle East. From national identity, to religious systems to patriarchal families, respect for the leader, authority or ¨father figure¨ is unquestioned. The values of the society, especially religiously based ones, are taboos that do not sustain critical inquiry. Indeed, in this scenario, the ability to truly see an outsider at ¨eye level¨, i.e. equal, is simply not there.

In the Middle East, these matters are simply seen as "the way things have always been, and will always be". However, this is a method of group survival with potentially terrible consequences in an age of globalization and weapons of mass destruction.

Whether in Israel´s relations to its neighbours, its desperate desire to preserve its identity or assumptions among some about being somehow superior to others, or in Hizballah´s grip on its members, motivating them to higher purpose through sacrifice, even death, cult behaviour continues to grip the region, hidden in the veneer of tradition and references to longstanding cultures and civilizations.

"You are our leader... We are your men!" (2). Indeed, most seductive of all, according to Deikman, is when belonging to a group comes with a divine calling. It makes the mission of sublime importance and eases the ability to maintain the tightness of the group, calling on members to act blindly in its favour. By devaluing outsiders and feeling supreme, the group can provide members with a sense of mission and meaning.

The benefits of belonging to groups that act like cults are many: comfort, security, belonging, and, above all, a sense of higher purpose that the group and leader deliver, often at any cost. Indeed, it is when security and comfort meet higher purpose that the cult becomes an iron-clad contract between individual and group.

The cost of cults is massive. Deikman calls it ¨diminished realism¨. We see it every day in the Middle East:

- 91% of Israelis supported the bombing of Gaza even though the results are profoundly uncertain, even possibly counterproductive (e.g. a post-war strengthened Hamas), and other methods of approaching the problem may not have been exhausted.

- Hamas is so sure of their ¨divine purpose¨ that there is little questioning of their goals or methods. All - rockets, bombs, terror – can be justified in the light of the group´s distant goals even if, again, the results are not there: Gaza remains under siege and in a profoundly abnormal condition despite Hamas's strategy.

Certainly, the record of progress in the Middle East is testament to a state of ¨diminished realism¨. It may not be at all impossible for Israelis and Palestinians to come to terms if certain taboos are sacrificed, i.e. if cult behaviour is recognized and reduced.

Cult behaviour does not just apply to religious or Middle Eastern groups. It appears in a more subtle fashion in companies, organizations, and even between friends. The difficulty is that devaluing outsiders, avoiding dissent and blindly obeying leaders is often unrecognized for what it is. Furthermore, the reality is that breaking out of the group can be terrifying. Being thrust out, "excommunicated", a heretic in one's own "family" - however understood - can mean that the most basic instincts of life or death are triggered.

Yet, ironically, the word 'heretic' is derived from the Greek 'hairetikos', meaning 'able to choose'. Indeed, many in the Middle East deny the possibility of choice and point to the dance of fate in their desperate destiny, where in fact longstanding and unconscious acceptance of cult behaviour may be at play. After all, no one really wants to be a heretic.

Developing awareness of the problem is not easy, but it is possible. Recognition of one´s own cult tendencies may be the beginning.

"The musk oxen gather in a circle to defend against the wolves yet there may be only other oxen outside the circle."

(1) "Hezbollah Seeks to Marshall the Piety of the Young", New York Times, November 21, 2008

(2) Ibid.

All text and photography copyright (c) John Bell and John Zada