“They made a desert and called it peace.”

-Tacitus

Jerusalem, 2015

The early morning light of Jerusalem is a divine gift. It shelters the holy city in its hollow.

The early morning light on April 12, 2015 was shattered by a roar in the sky and a great blinding light.

It was 5:00 a.m. As the sun began its rise above the Judean Desert beyond the Mount of Olives, the rocket soared, interrupting the sound of the rising birds. Its roar increased and all who were up at that hour looked up to see its tail of flame - until it stopped flickering orange, and fell directly to earth.

All those awake looked up to witness the event without knowing what it meant. Seconds later, the rocket spoke its tale: a great white flash blinded all onlookers. A blast knocked people to their feet, reverberating into the walls of the Old City and shattering the glass of the parked cars wide open.

All that was fragile, the vegetable stall, the ornate stained glass window, the human body, all of them shattered like a cookie in one’s hand. The crumbs of living beings were strewn about in trees and by curbs - their atomic shadows left on the kitchen walls.

The blast was quick and dirty. The air was sucked back in with the vengeance of a millennium of pain and suffering, all the way back to ground zero somewhere above the Via Dolorosa, in the Muslim Quarter. It took everything with it - walls, vehicles, lampposts and crushed them all together like dust in the bag of a vacuum cleaner.

As the grey cloud of radioactive tinsel settled on the city, no one was steady enough to think about what had just happened. The shock, the impossibility, caused whatever few survivors there were to just walk around and around, not caring where they were going, not knowing why they were still alive. A great suffering came upon the earth, and very many, close and intimate, fell in its wake.

Somewhere between the appearance of a red heifer, an architectural plan for a new Temple, the destruction of Iraq, the massacre of Nablus of 2010, and the chemical-terror fire in Tel Aviv three years after, the decision percolated in the minds of some leaders to send the rocket forward.

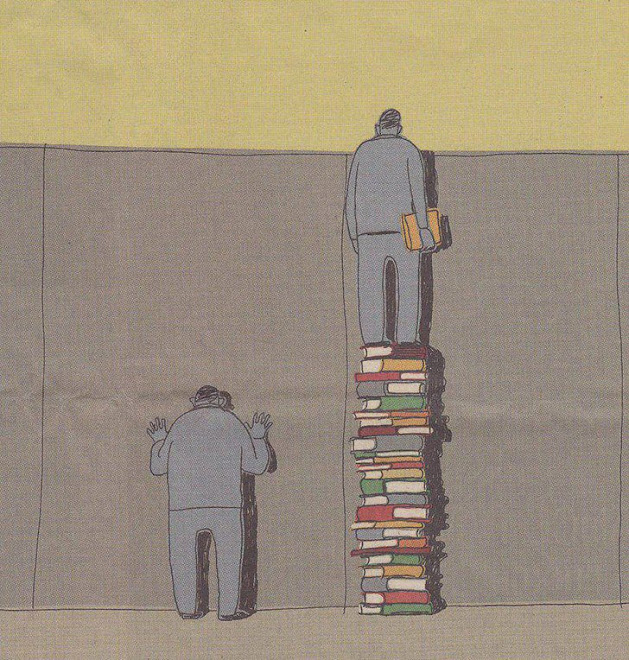

It came in the early morning light - that hour of greatest human frailty, of silent and lonely deaths in the hospital while those who cared had finally dozed off, when the darkest and most arid thoughts ran amok in the minds of the sleeping. And it came, in the push of a button, a "why not?" in the minds of leaders who understood well the consequences: total annihilation, the obliteration of the region in a series of nuclear spasms and an encroaching chemical soup. A mass suicide implicitly agreed to by the hundreds of millions living in the Middle East, committed by their leaders, after the pain and confusion of over sixty years of suffering, oppression and fear.

Jerusalem, the sacrificial lamb for Jew and Arab, would be no more. By noon that day, April 12, 2015, there would not be much left of the rest of the Middle East: Beirut, Damascus, Baghdad, Aleppo, Haifa, Tel Aviv – all destroyed in a frenzied exchange of weapons of mass destruction.

A few corners of the Ottoman wall of the Old City were left standing against all odds. The graves on Mount Scopus were engraved into the ground by the blast, and the creaking tower of the Holy Sepulchre was still hanging against gravity by a concrete thread. Mount Moriah remained, the Dome of the Rock blasted out of its octagonal foundation, its blue tiles strewn about the valleys around the city, including Ga-Hinnom, the valley of Hinnom, a word that signifies "Hell" in Arabic and Hebrew. The small bones of children now lay buried besides the old corpses. The grey dust of the living dead: the citizens of modern Jerusalem, Jew, Arab, Armenian and pilgrim, annihilated by a rocket from distant quarters. The messenger of a battle gone wrong, of men whose priorities had become the function of their fears.

The City on the Hill would be remembered in lore and legend. Its destroyers, dark pawns of a strange evil that visited man in the early 21st century, and its old occupiers and past courtiers, greedy nations who valued their tribal ways more than the ways of men - these now live on in the children growing up around the cypresses and Mediterranean oaks of the few lands untouched by the Great Cataclysm.

Text in this post copyright John Zada and John Bell 2008

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)