The village was originally called Taranje, before the arrival of the Kurds who changed its name to Ghajar, or 'Gypsies' in Arabic. It is very possible that a tribe of the Romani ended up there, as they did in valleys and plains throughout the world. Under the Ottoman Empire, Alawites from northern Syria settled in Ghajar, as well as two other nearby villages in the Golan: Za'ura and Ayn Fit.

The village was originally called Taranje, before the arrival of the Kurds who changed its name to Ghajar, or 'Gypsies' in Arabic. It is very possible that a tribe of the Romani ended up there, as they did in valleys and plains throughout the world. Under the Ottoman Empire, Alawites from northern Syria settled in Ghajar, as well as two other nearby villages in the Golan: Za'ura and Ayn Fit.Once upon a simpler time, a bus line connected Marjayoun in Lebanon to Qunaytra in the Golan. Ghajar was a stop on that route - its only connection to the rest of the world. Today, the town finds itself in a strange seclusion, surrounded by fields of land-mines to the north (placed there by Israel during its 22-year occupation of southern Lebanon), and a fence erected south of the village, similar to the electronic sensitivity grid Israelis have placed elsewhere to detect attempts to cross from Lebanon.

Today's Ghajarites are, however, well adapted to their context. They live in a large village with well-off homes, different in style and size from the poorer Lebanese villages to their north, or the tidy California-style spreads of Israel at Metulla and Kiryat Shemona to their southwest. Source of income of the village: unknown; "border enterpreneurs", if you wish.

The Ghajarites claim they are Syrian, descendants of a man who ran from trouble in the Alawite regions in the north-west of Syria, and who settled in this strange and barren corner. However, they also hold Israeli passports and speak Hebrew, with many of their children educated in Haifa at the Technion University or elsewhere - a function of their adaptation to Israeli rule since 1967. The Ghajarites claim allegiance to Syria, demand the fruits of citizenship in Israel, and want nothing at all to do with Lebanon, where half of them now technically belong.

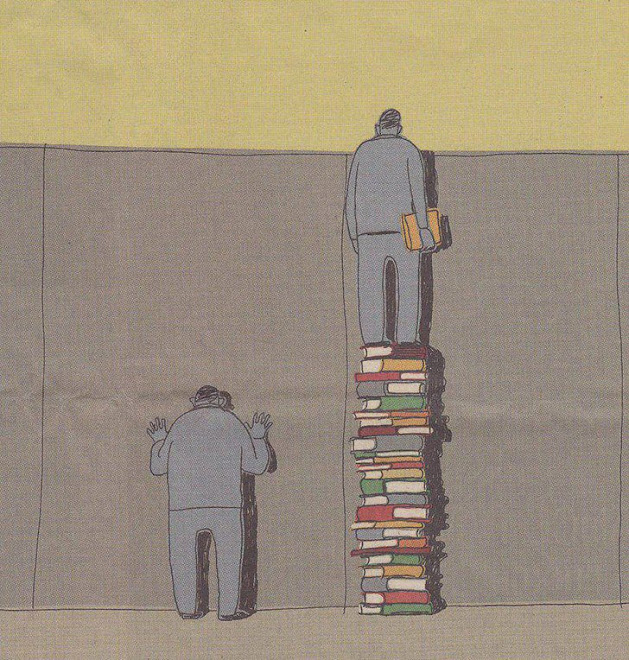

They are victims of war, the march of history, modern cartography and the borders that have carved up the Middle East. During the rush to create a line of Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, the UN partitioned the village into two sovereignties. Indeed, it may be that the partition of the village was decided under the pressure to complete the Israeli line of withdrawal from Lebanon, and may not present the most accurate picture of history.

Maps depicting Ghajar, including those made prior to the Israeli invasion of 1967, are very inconsistent. The 2000 partition may have been based on historical and cartographic errors; Ghajar could have been part of any of the entities created at the end of the Ottoman Empire: Syria, Lebanon, or Palestine (1). Indeed, Ghajar is an example of a general problem, the lack of exact border demarcation between Lebanon and Syria. Here, however, the problem is exacerbated by the human dimension: nowhere else does the border apparently cut through a village.

At one point, Ghajar became a flashpoint between Israel and Lebanon/Hizballah. Because the town was a potential infiltration point into Israel from Lebanon, the Israelis took it upon themselves to occupy the northern two-thirds of the village. The Ghajarites have demonstrated actively against being divided, fenced in, and handed over to countries where they do not belong.

Ghajar speaks to a day when political identity mattered much less, and when states did not measure borders to the inch. Certainly, these villagers were once the victims of marauding armies, and, no doubt, they swayed with the prevailing political winds to survive and thrive. But, nobody had previously thought of bisecting their village and its surrounding fields in the name of a proper border. That act took the brilliance and exactitudes of modern diplomacy.

Ghajar speaks to a day when political identity mattered much less, and when states did not measure borders to the inch. Certainly, these villagers were once the victims of marauding armies, and, no doubt, they swayed with the prevailing political winds to survive and thrive. But, nobody had previously thought of bisecting their village and its surrounding fields in the name of a proper border. That act took the brilliance and exactitudes of modern diplomacy.Like other unfortunate "political gypsies" of our time, including the Palestinian refugees, they belong nowhere, in a sense, at a time when everyone must belong somewhere, or suffer the consequences.

(1) This entry is based partly on the study by Asher Kaufman, "Let Sleeping Dogs Lie: On Ghajar and other Anomalies in the Syria-Lebanon Tri-Border Region."